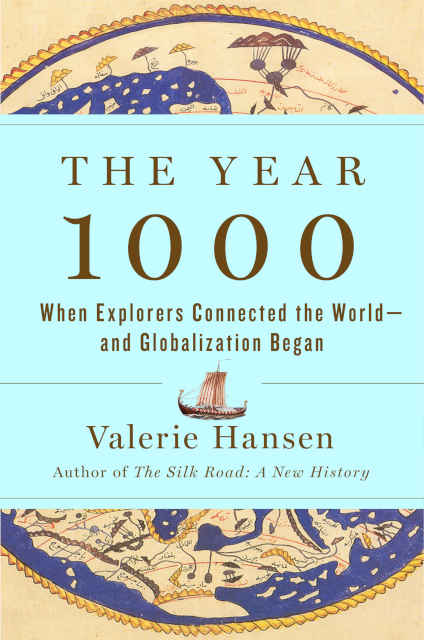

Taking a break from gun history for a while, I just finished Valerie Hansen’s 2020 book, The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World and Globalization Began. Great book, highly recommended.

While I can absorb a high volume of information in a short amount of time – a skill that benefits my career – I usually enjoy reading very slowly, marinating or mentally bathing in a good (usually nonfiction) book. The Year 1000 is the kind of book I love, full of fascinating anecdotes and illuminating a period of world history about which I know very little. Therefore it surprised me when I finished this book in about two weekend sittings. It’s just that good. I started dog-earing pages upon which something remarkable was mentioned and realized I was dog-earing every other page.

Hansen’s theme in the book is that events and circumstances surrounding the year 1000 brought an unprecedented level of trade between regions, and marked the first time where a trade network truly wrapped around the entire planet vis-à-vis the Norse exploration of North America. For the first time, even though we have no evidence of it happening, an item could plausibly be traded around the globe, arriving at the place it started through trickle-trading networks between adjacent regions.

The author is not claiming that long trade routes were unknown before this – we all know long trade networks have existed longer than any of us likely appreciate – we’re constantly stunned to find goods from far off regions in the archaeological record of what were imagined to be isolated and remote communities. What the author is relating is that these networks expanded in reach, reliability, and local impact: that goods from far off regions became more widely and routinely available due to increasing trade intensity, that local economies were finding it more profitable to produce goods for far off destinations than to cultivate crops and produce goods for their own immediate consumption or use. They could buy what they needed to subsist and then some with the money they made off of specialized commodities.

It was also around this time that the world started sorting itself into the broad religious categories of Roman Christianity, Byzantian Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism. Hansen provides many examples of regional kingdoms aligning themselves with the religions of more powerful rulers. These chosen religions seeped into the citizenry and displaced local pagan beliefs over the years. This formed a new identity – broadening the perspective of a people from seeing themselves solely as inhabitants of a region to people of a particular belief system that stretched over vast, vast distances. This is underscored by examples of alliances that are turned down on the basis of no shared religious tradition. The great world religions begin to really sort populations at a scale not previously seen.

The book is full of fascinating information about the Viking footprint in North America, the empires of Mesoamerica, and the contemporaneous events in the Mediterranean theater, the Middle East, central Asia, and Eastern Asia. I found the book at its most interesting when it moved to the central Asian empires of the Karakhanids, the Ghazavanids, and the Northeastern empire of the Liao dynasty. Hansen perceptively offers a section in the back of the book entitled, “Want to Learn More?”, with pointers to additional books and resources for digging into topics she presents across various chapters.

It’s remarkable how much of the book is focused on the slave trade – it reminds us how the scourge of slavery has been a grim companion of human history for as long as we can remember; that every society seemed to take part in it; and that Europeans hardly had any monopoly on it — rather contributed greatly to the supply side for much of the dark ages. Hansen points out the linguistic connection between the ethnonym Slav and the word slave, and that the root for one of the many Arabic words for slave, saqaliba, is related to their term for the geographic region of Europe. Ibn Fadlan gets a cameo reference in this book, whose work I would highly recommend reading. Ibn Fadlan’s journal describes a world in Eastern Europe that I could no better relate than saying it was like a bunch of violent motorcycle gangs running around through the forest – catch as catch can and God help you during “slaving season”. Hansen’s description of the slaving economies between Europe, Anatolia, Africa and the Middle East does nothing to dispel this impression.

This is a difficult post to wrap up, but it’s a great book and I’d highly recommend it if you’re a history nerd like me.