Welcome back! When I started this, I literally thought one article would do it, but here we are on part 3.

If you’re interested, in Part 1 we explored the the Sharps New Model 1859 Navy Carbine based on its outward physical appearance.

In Part 2, we took a trip through time from 1967 to essentially present day, looking at how the authoritative Sharps scholars have regarded this gun and how new research has revealed more about their history.

Now, in Part 3, we get to the good stuff: where I get to take all that great information discussed in part 2 and reconcile it, mush it all around and try to draw some conclusions.

We ended the last article with Roy Marcot’s information that seemed to conclusively give us an origin story of the carbine, tying it directly to the Mississippi Squadron.

The Mississippi River Squadron

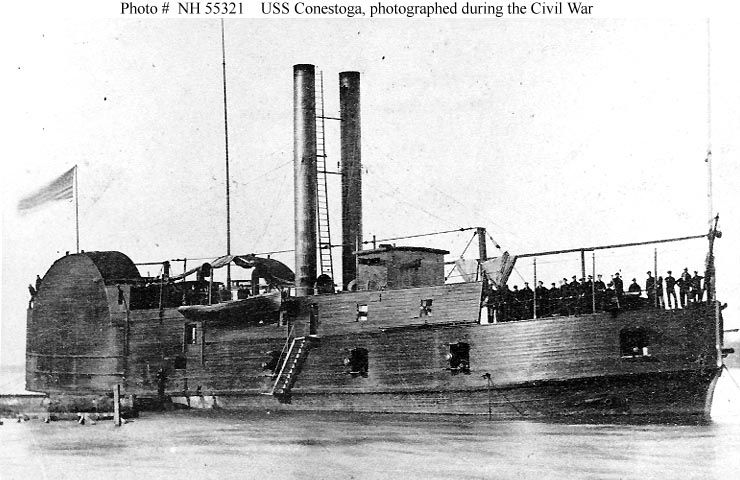

What was the Mississippi Squadron? This refers to the Mississippi River Squadron, which was constituted on May 16, 1861, by the Army, not the Navy, just a few months before our carbines were requested. The Squadron was an Army operation, even though it was commanded by Navy officers. It is colloquially known as the “brown water navy”, in reference to its theater of operation, “Ol’ Muddy”. In the summer of 1861, the Squadron was comprised of “timberclads”, precursors to the better known “ironclads”. The USS Conestoga, pictured above, is a converted civilian tug boat, reinforced with thick oak armor and carrying smoothbore guns. This exact boat was part of the Mississippi River Squadron in ’61. These boats served as transports, vehicles for raiding parties, artillery support for ground operations, and of course the active security detail of the River. The Squadron was eventually taken over by the Navy in June of 1862, and renamed the Mississippi Marine Brigade.

This isn’t the first time the Squadron has come up in connection with these guns. Recall that McAulay found a letter from the Secretary of Navy requesting permission to stash the guns from the Squadron in St. Louis in 1865, just months before their official demobilization.

Our book says that these carbines were requested for the use of the Squadron, and the paper trail seems to support that idea. Why no brass furniture? Well, these rifles were for freshwater service, not corrosive blue water detail in the hands of Marines. Why no saddle ring? They weren’t going to be used on horses. It all seems to fit elegantly.

The Mitchell Contract and Serial Numbers

Marcot also gives us a connection to the Mitchell contract – speculating that based on contemporaneous serial numbers, the “Nelson contract” [my term] may have been fulfilled using leftover rifle receivers from the Mitchell contract. The “Mitchell contract” refers to the Sharps agent in Washington, D.C., John Mitchell. In June of 1861, the Navy requested a batch of rifles through Mitchell, and this batch of New Model 1859 rifles is now known as the Mitchell rifles, or rifles related to the Mitchell order, or Mitchell contract. The Navy wanted 1500 rifles delivered by the end of the month, which was an aggressive timeline. Nonetheless, they were all delivered by August at least, which is impressive. These rifles were all in the low 40,000 serial number range, according to McAulay. Marcot offers us some finer resolution, stating that they are known to exist up into the 42,000 serial number range. He states that the Navy carbines are “in the 43,000 range.” Marcot’s paper trail and serial number data seem to indicate that the production of the Mitchell rifles and the Squadron carbines overlapped, and it’s not too unreasonable for him to infer that the leftover rifle receivers and stocks may have been used to produce the “Nelson order” for the River Squadron.

Okay, I’m going to stop calling these “Navy Carbines” and start referring to them as “Nelson Carbines”. It’s not really a “thing” publicly, but just to keep things straight in my own head, this reference makes far more sense to me. These carbines were requested for use by the Army, not the Navy, and by Nelson.

I would like to note that we have some conflicting data here on serial numbers. McAulay states that the Nelson carbines were seen in the 40,000 to 43,000 range. Marcot states that the carbines are in the 43,000 range, however in the same book (page 33) he has a great photo of one of these guns listed as serial number 41678. That’s close to my own, which is 41694. Look, dear, you’re almost famous!! I have seen photos of others in the 43k and 44k range. The carbine that Hopkins inspected in detail was in the 44k range. It seems to be an agreed upon fact that only about 300 carbines were produced in total. Recall that Sellers himself identifies a Nelson carbine in the 47,000 range!

The Conversions

I think it’s safe to say that at least 190 of the original 300 carbines were converted (based on the correspondence from Ft. Union, New Mexico, mentioned in Part 2). I also think it’s safe to say that not all of the 300 were converted. I have seen photos of these carbines still in their percussion configuration. The carbines that Hopkins examined in 1967 were unconverted.

Of those that were converted, I’ve never seen one that wasn’t an “1868” conversion. Put another way, I’ve never seen one of these converted to a Model 1867. The 1868 conversions have a new notch cut in the breech, and a “cam-action” to lift the firing pin away from the breech that’s different than the Model 1867’s spring-based mechanism. Sellers tells us that only 1900 type 1867 conversions were done on carbines, and these were the first conversions performed. When considered in the context of some 30,000 carbines converted, and that several thousand carbines had already been converted before the Nelson carbines would have showed up at the Sharps factory — if shipped from St. Louis — it seems unlikely that any type ’67 conversions of the Nelson carbine would exist.

I also suspect that the stocks were replaced on these Nelson carbine conversions. Based on an admittedly small sample size, it seems that the unconverted Nelson carbines have patch boxes, and the converted ones do not. I could be entirely wrong on this, but it seems like a pattern. It also seems unlikely that the original order would have been fulfilled with inconsistent stock design – some with a patch box, some without. In the last article we mentioned that in the 1863 pattern, no more patch boxes were included, and by the New Model 1859, they were starting to disappear. I know examples of converted carbines (not Nelsons) that do retain a patch box. However, it’s notable that the Army field guide, “Description and Rules for the Management of Sharp’s Carbine. 1868.” does not seem to itemize a patch box in its detailed list of parts, components, and screws.

Marcot tells us that the contract to convert the Sharps carbines to metallic cartridges in .50-70 was signed by Sharps on October 26th, 1867, and counter-signed by General Dyer on November 2nd, 1867. On November 7, 1867, David F. Clark was appointed to inspect the work product. The first conversions were being delivered back to Springfield Armory by February of 1868.

Sellers tells us that on July 3, 1868, all the carbines stored at the St. Louis arsenal were ordered to be sent to the Sharps factory for conversion, and on July 23rd, they were so shipped. This was done in response to Sharps notification that they were running low on stock of percussion arms to convert. He also adds the frightening note:

“The method of shipment somewhat concerned the officials at the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company. The carbines were piled loose in a boxcar and shipped and no packing of any kind was used. A few carbines that were still in the original cases were shipped in them. The carbines that had been issued were all shipped loose in the boxcar. Consequently, most of them were in rather bad condition when they reached Hartford after 2,000 miles over the railroad.”

Sharps Firearms by Frank Sellers, 1969.

In Roy Marcot’s 2017 book, Sharps Firearms: Early Sharps Metallic Cartridge Firearms and Model 1874 Sporting Rifles (typically billed as “Volume 2”) we get a lot of detailed information on the conversion timeline. I draw from this resource in the info that follows.

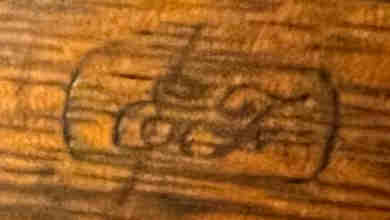

According to Marcot, as late as September 7th, 1869, Edwin Ferrar, an arms inspector, was sent to help David F. Clark with the approval of the conversions. My own example of a converted Nelson carbine has both the “DFC” cartouche on the left side of the stock, and the “EF” cartouche on the wrist. This would tell us that some or all of the Nelson carbines were converted no earlier than early September 7th, 1869.

A side note of import, in the sense that I cannot reconcile it, is that the invaluable 2016 book, “U.S. Military Arms Inspector Marks”, by Anthony C. Daum and Charles E. Pate, does not believe Edwin Ferrar to be the ‘owner’ of this cartouche, but makes the case that this mark belongs instead to Edward Flather, a civilian employee of the Armory. Daum and Pate cite work by R.C. Kuhn on inspector marks published in The American Rifleman and The Gun Report attributing this mark to Ferrar, but lay out reasons for why this they believed it unlikely. In their book, the cartouch is listed as EF #2. Having missed any detailed discussion of this question of attribution in Marcot’s work, I do not know how Marcot arrived at the conclusion that it was Ferrar, though I’m sure he has his reasons – perhaps he has seen the order itself.

Interestingly, Marcot also tells us that a month later, it was reported that out of 33,321 percussion carbines sent to the Sharps factory, only 1,131 carbines remained to be converted. It’s conceivable that some or all of the Nelson carbine conversions were as yet unconverted by Q4 1869.

Sellers tells us that of the 100,000 Sharps purchased since 1851, only 50,000 were on hand by the end of the War. Of these, 32,000 were converted. That’s a 50% loss, and another 46% rejection rate. How many of the 300 carbines, if issued, survived the war and the boxcar ride? Well, 190 doesn’t seem so crazy.

The Unconverted

What would have happened to the unconverted? Sellers also tells us, in the context of small-arms generally, that it was military policy to allow the veterans to purchase the equipment they had used during the War. Other guns may have been given over to state militias. The military had a habit of selling unwanted weapons to third parties for resale, such as Joseph C. Grubb and Company, or Schuyler, Hartley & Graham, who then sold them to the public or other nations. If I understand Sellers correctly, those old 1900 type-67 conversions were sold off to Schuyler in 1871. Could the unconverted Nelson carbines have been sold off either at the end of the war, or after the boxcar ride to Sharps? Recall that Hopkins said the owners of the two unconverted carbines he was examining were understood to have come out of Benicia Arsenal in California. It’s hearsay, so we can’t lean too heavily on it, but if that’s true, it’s an interesting factoid – Benicia was a staging area for the Union during the Civil War, and also home to the camel corps. Make of that what you want – could some of the Nelson carbines been shipped to California during or after the war? Hopkins notes the furniture was color case hardened, which I wasn’t aware to be the finish on the original percussion guns. Were these refinished? Mysteries within enigmas.

In addition to the absence of characteristics of a conversion mentioned above, I would expect the unconverted Nelson carbine to not have the EF and DFC cartouches on the stock. I would expect it to measure somewhere around .52-.53 bore diameter. I would expect it to have a patch box. I would expect it to have an un-scalloped hammer. I would expect it to obviously have an action set up for percussion primers. Marcot states that some of these evidently have a stock with USN / I / F.A.R imprinted in three lines just above the patch box, and that some have C.W.H. stamped on the left side of the barrel near the receiver. I’ve not seen this, but again, low sample size.

Forgeries and Fakes

I cringe to even open this can of worms, but it’s a fact – fakery is endemic in any collecting hobby, and it’s particularly bad in the gun collecting world. Cutting down a New Model 1859 rifle barrel to carbine length and reworking the forearm is not inconceivable. In fact, it’s what Hopkins suspected was going on in 1967. Could some of these “Nelson carbines” be fakes? Almost certainly – any degree of protection they have is owed to their near complete obscurity, but Flayderman’s statement, “Worth premium if authentic,” is a dog whistle for the fakers. Is my gun a fake? It complies with McAulay’s serial number range, but it doesn’t comply with Marcot’s range, and particularly doesn’t comply with his idea that these were produced after the Mitchell rifles, unless you assume that there was a big grab bag of pre-stamped rifle receivers in a box from which random ones were pulled to fill contracts.

For the record, I believe this is generally the consensus – that Sharps serial numbers are not sequential within a contract/order. But let’s underscore that if we take the upper and lower bounds of serial number ranges listed and the examples cited by our authorities, we’re talking about 41-47k. That’s a wide range of rifle receivers to be in the parts bin, it seems to me, but who am I? Just some guy.

Examining the question of fakes and how to determine a proper Nelson carbine from a fake probably deserves its own article at some point. The questions would probably run along these lines: what engravings or impressions are particular to the Nelson carbines that aren’t seen on the Mitchell rifles or other New Model 1859 rifles? What’s the story with patch boxes? What visible features change between the Nelson carbines and rifles? These too can be faked, but such answers might at least allow us to identify obvious fakes. What are the obvious signs of a barrel being cut down, a new front sight dovetailed in? What’s the barrel caliber? Does the front end of the forearm look different?

Were These Guns Ever Issued?

Marcot speculates that they were never issued to the field. He goes on to say:

“The Navy Bureau of Ordnance records and Deck Logs from the National Archives do not show these carbines being issued to the Mississippi Squadron. Ships logs of this squadron during the Civil War do not show receipt of New Model 1859 Sharps carbines, although several vessels were armed with Sharps New Model 1859 Military Rifles. The 1866 official Navy inventory listed only a few Sharps Model 1855 carbines. It appears that the Sharps New Model 1859 carbines may have remained at the New York Agency storage facility throughout the war. The carbines would not have been issued to Federal Cavalry troops because of lack of a sling ring.

Sharps Firearms – Volume 1. The Percussion Era, by Roy Marcot, Ron Paxton, and Edward W. Marron. 2019.

The Sharps New Model 1859 Navy Carbines found in today’s collections are typically in very good or better condition, confirming the view that they were not issued.”

Okay, so just to get it out of the way and then be done with it: “typically in very good or better condition, confirming the view that they were not issued.” – or alternatively this shows that some are refinished and falsely-aged forgeries. It’s healthy to be ever the skeptic, and forgery is another explanation for “too good to be true” conditions. Okay, that’s all I’m saying about that issue until we have a chance to deep dive it in a different article. I’m not saying many are fakes, I’m not saying serial numbers outside Marcot’s range (including my gun!) are fakes. I’m just saying that there are still unanswered questions about these guns, and for which we must allow that forgery offers some explanation. I said I was done, let’s move on.

Marcot offers other compelling reasons for speculating that these guns were never issued:

- The guns don’t show up in deck logs.

- The ships don’t record receipt of these guns, even though they show receipt of others.

- The Navy inventory in 1866 doesn’t itemize these carbines.

- The guns were worthless to the cavalry after the war.

In criminal trials, the burden of proof is “beyond a reasonable doubt.” In historical analysis, as in civil trials, the standard is often “the preponderance of evidence”. I would say Marcot’s argument meets the “preponderance of evidence” standard, at least insomuch as we cannot easily dismiss his theory.

On the other side of this debate, we know that the Navy records of guns could be light on detail and even incomplete. On civilwartalk.com, user Cannonman1 helpfully pointed out in 2021 another book by McAulay, “Civil War Small Arms of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps”, showed an ironclad, U.S.S Cairo, was listed having .44 Colts, and no other weapons, and we know this is likely an incomplete list, so it seems to impugn the accuracy of such logs. I am also aware of instances where guns in Navy logs are only referred to by make and caliber with no other detail. So can the logs be relied upon? In a criminal trial, we’d get them tossed (but this isn’t a criminal trial).

We also know the guns from the erstwhile Mississippi River Squadron (by this time, the Mississippi Marine Brigade) were brought ashore to an Army installation in 1865, the Jefferson Barracks Military Post. This may be all the reason we need for them to have not show up in an 1866 Navy inventory. Were other weapons stored here listed in that Navy inventory? I simply don’t know, but let’s add it to the list of open questions.

The case for service in the Civil War is probably better than the case for service in the Indian Wars. I’m going to start with the Indian Wars because I think it’s a little easier nut to crack. The conversions, we know, were performed in 1868, but the Nelson carbines weren’t converted until Q3-Q4 1869. In 1869, we know some converted carbines (surely not Nelson’s) were already in Ft. Union, New Mexico, and being distributed to Third Cavalry, who were trading in their Spencer repeaters for the 50-70 cal Sharps. In 1870, Eighth Cavalry was getting “new-to-them” converted carbines. I’m getting this information from an article about Ft. Union, here.

In 1871, the military storekeeper of Ft. Union, William Shoemaker, writes a letter stating that 190 of the carbines they received had no saddle ring. Marcot tells us that in the mid 1870’s (guessing 1874-5) all of the 1868 carbines were auctioned off as mil-surp, and that these guns ended up flooding the civilian market. For the record, in 1882, any remaining Ft. Union material – all of it – was dispersed to Rock Island Arsenal and Lowell Ordnance Depot. So these guns had from late 1869 to 1874, let’s say, to be issued to troops. The ones in New Mexico were still unissued as of 1871, but still in military possession. So the New Mexico lot of converted carbines had from 1871-1874 to be issued. I tend to lean towards Marcot’s theory that at least after conversion, these guns were not issued for service in the Indian Wars. Consider that in 1870 the Army was already issuing model 1870 carbines out to the field for trials. The Model 1868 Sharps carbines with relined barrels were considered rather poor performers, though at first evidently preferred over the Spencer carbine by many (including Shoemaker). Barring some evidence – an Indian captured Nelson carbine, a Nelson carbine with saddle wear, a Nelson carbine with other military engraving (infantry or cavalry company), etc., we just don’t seem to have any evidence they were put out in the field. Again, preponderance of evidence.

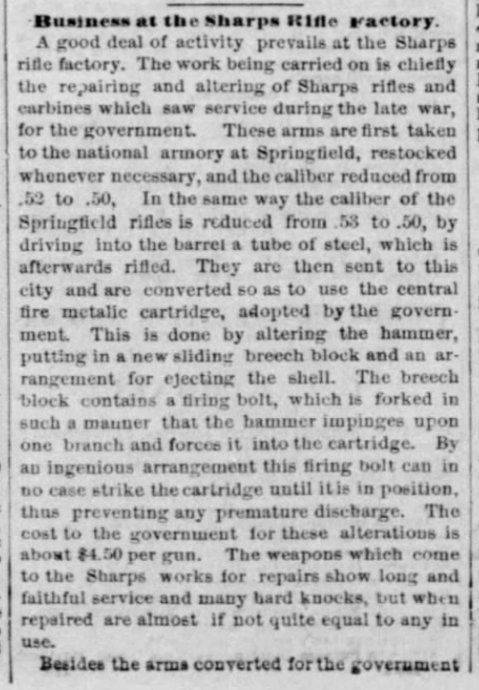

Civil War service is a topic I’m a bit more optimistic about. The unconverted rifles I’ve seen are not in the greatest shape. The Hartford Courant brags about the quality of the repair work performed by Sharps, stating on May 24, 1869, “The [original] condition of these guns was decidedly bad: most of them were rusty, and altogether they possessed a thoroughly demoralized appearance; but the repairs have been complete, and it is difficult to tell, in looking over those ready for re-shipment, and comparing with new weapons, which have seen no service.” Since these conversions were likely not deployed to cavalries after making it to Ft. Union, perhaps this explains why we see the conversions in such fine shape today.

A big question that needs an answer is whether these rifles were in St. Louis. Why? If the guns were in St. Louis, it greatly improves the case for them having been deployed to the river squadron during the Civil War. If they never made it to St. Louis, they probably did sit in crates in New York. We can only speculate, but I think there’s a good case to be made that they did arrive at St. Louis. I’d make the case with a few points that I’ll expand on, each in turn: A) I don’t think the deck logs are dispositive; B) the rifles were converted later rather than earlier in the contract’s timeline; C) only a subset of carbines were converted; D) the unconverted I’ve seen are not in the greatest shape.

A) My skepticism of relying too much on the deck logs is noted earlier in this section.

B) Shoemaker at Ft. Union had already been handing out conversions for a year or more before complaining about the Nelson carbines in 1871. To me this means they weren’t some of the first carbines to arrive at Ft. Union. In turn, this would imply that they weren’t the first to arrive at the Sharps factory for conversion between December 1867 and June 1868. In fact, we know they were not converted until 2H1869. Backing this up, there are no pattern 1867 conversions of Nelsons. Here’s the kicker: I suspect that if the rifles were in New York, they’d have been some of the first to arrive for conversion and therefore some of the very first shipped out for reissue – New York is close to Connecticut, after all and guns there would certainly arrive more quickly than a 2000-mile train ride. If the Nelson carbines were later arrivals at Sharps, there’s a better chance they came in from St. Louis or elsewhere.

C) If all 300 carbines sat in New York, never deployed, but were sent to Sharps for conversion in new-in-box (NIB) condition, it seems odd that we’d have unconverted carbines today. Why would they have rejected some of the NIB carbines? Sharps had every incentive to convert everything it could get its paws on and complained every time they were close to running out. It’s also perhaps odd that only 190 would end up in Ft. Union. It’s an odd number. I would allow that some conversions would have been shipped to other forts/arsenals, but why not an even 160 or 180 or 200? Is it more likely that Sharps/Springfield rejected the worst of the bunch, implying damage from field use?

D) I’ve not seen a lot of unconverted carbines, but most of those that I have seen are not in spectacular condition.

You and I can contest any of these points – we can only speculate barring more evidence. I just don’t think we can let Roy Marcot’s conclusion about their issuance rest without acknowledging the counterpoints, and I think those counterpoints are strong enough to give the question of service during the Civil War more consideration.

Open Questions

So I hope y’all can see that there are still plenty of unanswered questions for collectors to research. If you’re lucky enough to have access to the National Archives, specifically things like Record Group 156 and others, you may be able to find additional period correspondence or inventory data that would shed light on some of these questions. If you live in Missouri or New Mexico – or California, for that matter – you may have opportunities closer to home to chase down some of these leads.

If you have further information or would like to offer corrections to anything I’ve written, please feel free to comment below. I never claim to be an expert on this stuff, just puzzling through the work of others to learn more.

This was a great source of information. I obtained a Navy Sharps in the 44k range, with both EF and DFC cartouches, no saddle ring, in good shape, 50-70 conversion. I like to add that I have signs of slight saddle wear on my stock, this could have been from the Cavlary, or from private use after.

Hey cool, thanks for the comment, Mike! Congrats on finding one. I would also assume no patch box in the stock, correct? Always neat to hear from someone else on the planet that is interested in this stuff. Very happy to hear the info was helpful. Cheers!