In Part 1 of this journey, we looked at a gun that turned out to be a Sharps New Model 1859 carbine. It lacked the ring and bar typical of a cavalry carbine, and didn’t have any brass furniture typical of a Navy contract. Nonetheless, these guns are colloquially known as the Sharps New Model 1859 Navy Carbines, which turns out to be a bit of a misnomer. I mentioned earlier that the true history of these guns wasn’t really known until several years ago, and in this article we’ll get into that history.

When it comes to the history of Sharps guns there are a few recognized books that constitute our general reference library. I list only those that apply to this gun in order of their published date:

- (1967) Military Sharps: Rifles & Carbines, Volume I by Richard Hopkins

- (1978) Sharps Firearms by Frank Sellers.

- (1991) Civil War Carbines, Volume 2. The Early Years by John D. McAulay.

- (1996) Civil War Sharps Carbines & Rifles by Earl J. Coates and John D. McAulay.

- (2007) Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms, 9th Ed. by Norm Flayderman.

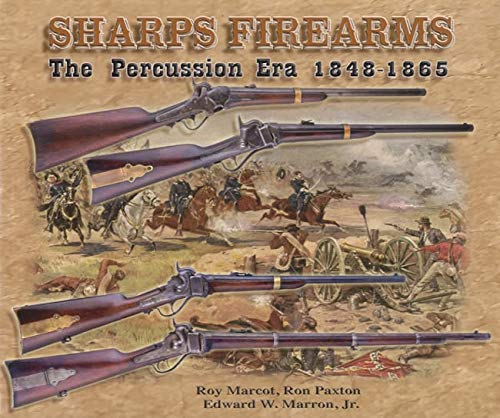

- (2019) Sharps Firearms – Volume 1. The Percussion Era by Roy Marcot, Ron Paxton, and Edward W. Marron.

If you know of more books that discuss this gun specifically, I’d love to know about it. I know McAulay has one or two more books out there with some overlap, but not sure if they have anything his other books leave out. We’re going to take a tour through time and watch how the iterative improvement of research from dedicated collectors over the years has evolved our understanding of this gun.

In 1967, Richard Hopkins wrote the following about Sharps New Model 1859 Navy Carbine:

“Two of these carbines were viewed personally and found to be identical. A third specimen has been reported; but no opportunity has arisen for a detailed inspection. The two models examined show approximately the same amount of wear. These three reportedly came from Benicia Arsenal [California]; very little is known about this variation and nothing official has yet been found that can substantiate the use of this model by the United States Navy. Until further and conclusive evidence is found to verify the issuance of this piece to the Navy, it should be considered as nothing more than a reworked rifle, an interesting variation, but surely not made of gold.”

Military Sharps: Rifles & Carbines, Volume 1 by Richard Hopkins, 1967

At the time, Hopkins referred to this gun as the “Sharps New Model 1859 U.S.N Carbine”. He notes the unusual lack of a saddle ring, and notes that the receiver, lock, barrel band, breech block, patch box, lever, buttplate and trigger plate are color case hardened. The caliber is listed as .52 and the action type is listed as percussion. So we can guess that what Hopkins was looking at is an unconverted variant of our gun. The .52 caliber is the “Sharps” caliber, and the conversions moved these to 50-70. Obviously the percussion action predates the conversion to a firing pin for metallic cartridges, and I suspect the patch box went away with conversions, but I’m drawing my own conclusion about this last point based on samples I’ve seen. Hopkins guesses the serial number range to be in the 44,000’s, and was looking at one numbered 44,010.

It’s notable that in Hopkins’ exhaustive listing of markings on the weapon, he does not list any markings for the Navy. However, he doesn’t list any inspector’s marks on the wood, keeping his list limited only to the metal stampings of patents, models, and manufacturers, so this may not be as valuable an omission as it first seems.

But clearly Hopkins was somehow associating this carbine with the Navy, even though he places great emphasis in his write-up that there is no evidence for this association. I can only assume that at this point the Navy provenance is gun show lore, probably a logical conclusion from comparing them to Navy carbines of the past. Hopkins is clearly skeptical, though. In fact, he says, “[this gun] should be considered as nothing more than a reworked rifle . . . surely not made of gold.”

Ouch. He’s basically saying he thinks these are cut down rifles – the barrel and forehand grip modified to be a carbine after they left the factory. Since the rifles and carbines used the same action and the same stock, this theory is just as valid as the “Navy carbine” theory at the time, perhaps more so considering the lack of any documented Navy connection. Hopkins was a skeptic – always a good trait for a gun collector.

Frank Sellers is one of the eminent Sharps scholars. His well-regarded book from 1978 addresses this gun merely as an aside. Keep in mind this is still over forty years ago.

“In addition to the carbines sold directly to the government by Sharps, there was a considerable number sold to them by private arms dealers and organizations, mostly during 1861 and 1862. The government purchases on the open market were allowed to pay up to $35 for Sharps carbines and $47 for Sharps rifles.

[Picture shown]

New Model 1859 Carbine, serial No. 47,148, with iron furniture; note single sling swivel on the butt. These carbines with only single sling swivel and no sling ring bar, were made for the Navy and took a sling which was tied around the barrel on the front end.”

Sharps Firearms by Frank Sellers, 1978.

His example is serial number 47,148. Note that he states these were “made for the Navy”. He is likely basing this on prior orders for the Navy – they ordered their carbines specifically with no sling ring bar, and a single sling swivel. This is a logical assumption and for most of the last fifty years, this was gospel. Why no brass furniture like on the New Model 1859 rifles? Mere details. There may be other research that was published between Hopkins and Sellers that helped the Navy connection theory. I haven’t poured through all my Gun Report magazines of the time to see if anything is there. Putting it on the to-do list.

In 1991, John McAulay offered us more information about these guns, building on Sellers’ starting point. Clearly, the hunt is on for answers:

“In the early days of the war, the U.S. Navy purchased a number of Sharps carbines on the open market. While the number and from whom they were obtained is not clear, they may have come from the Philadelphia firm of Joseph C. Grubb and Company. On June 18, 1861, a number of Sharps were purchased by James S. Chambers – Navy Agent in Philadelphia – from Joseph C. Grubb and Company. While this is a possible source of the Navy Sharps, the number purchased is hinted at through some post war correspondence. On January 17, 1871, the commanding officer at Fort Union Arsenal stated that he had one hundred ninety of the Navy style Sharps carbines – made without a saddle ring and bar on the left side of the frame. These one hundred ninety Sharps had found their way into the Ordnance Department and were part of those carbines converted to 50/70 centerfire. Since few of the percussion carbines are encountered, and it appears that most were converted to centerfire, the Navy’s original purchase for the New Model 1859 Sharps probably did not exceed three hundred carbines. As previously stated, the major characteristic of the Navy New Model 1859 Sharps carbine is that it was not equipped for a saddle ring and bar and that many are found with a large lanyard ring located at the toe of the butt stock. Serial numbers on most of the Navy Sharps found are between 40,000 and 44,000.”

Civl War Carbines, Volume 2. The Early Years by John McAulay.

So from this bit of info, we add the following information:

- We still don’t know where or how these guns were purchased.

- We are still assuming they were made for the Navy.

- Maybe a Navy purchasing agent was involved, as a number of guns were purchased from a third party about that time.

- In 1871, 190 of these were in Arizona at the Ft. Union arsenal.

In hindsight, this was an odd set of facts. In part 1, we noted that these guns weren’t modified cavalry carbines — the receivers and stock were manufactured without consideration for the saddle ring and bar. So there must be a story there – if they were made to order (not cut-down rifles as Hopkins suggested), they were made under contract and likely wouldn’t have wound up in the hands of a third party for resale without a paper trail. Nonetheless, this is a lead.

In 1996, Coates and McCaulay provide the fruits of further research:

“[Major] Benton closes the letter [with regard to the Ft. Union guns] by saying that these arms were originally made for the Navy and he had no idea how they came to be in the possessions of the Army. The answer to this question can be found in a letter written by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles dated June 19, 1865, to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. In the letter, Welles requests permission to allow the storage of naval guns, ammunition, and stores at Jefferson Barracks near Saint Louis. This naval ordnance was being turned in from vessels of the Mississippi Squadron. The request was made because the Navy did not have any convenient place for storing these items….Three years later when the St. Louis Arsenal was directed to send the Sharps carbines and rifles to the Sharps factory for alteration, the Navy Sharps were also sent for conversion.”

Civil War Sharps Carbines & Rifles by Earl J. Coates and John D. McAulay

So here we’ve added a few more bits of information:

- A source with the Springfield Armory [Benton] states that these guns were made for the Navy.

- A letter implies that the guns coming off the Mississippi squadron after the war were being stored near St. Louis at an Army post (Jefferson Barracks are down river about 10 miles from St. Louis).

- St. Louis was directed to send Sharps percussion weapons in their arsenal to the Sharps factory for conversion.

- Presumably after conversion the guns were sent out to Ft. Union, which had become a bit of a dumping ground for weapons.

Again, in hindsight, we can see that these dots are only loosely connected – we’re speculating based on the information at hand, but the story is getting filled out. More questions are raised: do we know these carbines were given to the Mississippi squadron? Do we know these carbines came in to St. Louis? The letter from Welles does not itemize these carbines, but talks about guns in the abstract sense only.

In 2007, the latest (and last) edition of the excellent Flayderman’s Guide catalogs the New Model 1859 Navy carbine variant as 5F-019, and describes it as follows:

“New Model 1859 Carbine; iron furniture with patchbox. Approximate quantity manufactured 30,000. Early 1861 the Navy purchased small lot (quantity and source unknown) not fitted with saddle ring and ring bar; serials in 40,000 to 44,000 range. Worth premium if authentic.“

Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms, 9th Ed., 2007.

It seems likely that Flayderman was relying on the sources we already discussed, principally McAulay’s work in 1991.

Finally, in 2019, Roy Marcot, et al, threw a major contribution on the table concerning this weapon:

“One of the true mystery carbines of the Civil War was the New Model 1859 Sharps carbine known as the ‘Navy Model.’ The wartime facts around the carbine remain vague. From the start of the war to the end of September 1862, the Federal Army commanded the inland rivers, including the Mississippi River. The Army Ordnance Department purchased and armed the naval vessels with Army crews led by Federal Navy officers. In the spring of 1861, William Nelson was sent by President Lincoln into Kentucky to organize and recruit for the Union cause. In July, from Cincinnati, Nelson wrote to the War Department requesting 300 Sharps carbines for the Mississippi Squadron in the process of being formed by the Federal Army.

Nelson’s request for 300 Sharps carbines was sent by the Ordnance Department to the Sharps Rifle Mfg. Company. At this time, the Sharps factory was in the process of finishing the Navy’s “Mitchell order” for 1,500 Sharps New Model Military Rifles. The Mitchell contract rifle serial numbers are found up into the 42000 range. The serial numbers of the New Model 1859 Sharps Model Carbines are in the 43000 range. Since the carbines were for the Federal Navy they had no use for a sling bar on the receiver, it is possible that the factory took the leftover parts from the Mitchell contract to fabricate the carbines.

The New Model 1859 Sharps Navy Carbines had a rifle receiver and rifle buttstock with sling swivel, and a standard carbine barrel. The 300 carbines were sent by the factory to the New York Agency, where they were inspected by the Army inspectors. An inspector’s cartouche was stamped on the left wrist of the buttstock. Army records indicate that 300 Sharps carbines were purchased for the Navy on September 3, 1861 at a cost of $30 each.

Sharps Firearms – Volume 1. The Percussion Era, by Roy Marcot, Ron Paxton, and Edward W. Marron. 2019.

This is pretty solid information, and gives us a new set of facts:

- William Nelson – wait, let’s pause here for a sec.

No, we’re not talking about Willie Nelson, but William “Bull” Nelson, an accomplished Navy officer who served in the South Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean. At 6’2″ and 300 lbs., he cut an imposing figure. He joined the union cause when the civil war broke out and was credited with keeping Kentucky from aligning with the Confederacy. Later in the war he was mortally shot through the heart by another officer during an argument – guy flicked a wad of paper in his face, he back-handed the man, man shot him. Since that’s a tangent from this article, I’ll just point you to the Wikipedia article here, which is a fascinating read. Incidentally, the guy who shot Nelson was never tried or convicted, owing to the Union’s desperate need for officers. That same guy would go on to become the first territorial governor of Alaska. Was that a backhanded compliment owing to this messy affair? I don’t know.

“Send for a clergyman; I wish to be baptized. I have been basely murdered.”

William “Bull” Nelson, Sept. 28, 1862

Anyway… rewind one year. President Lincoln sends Nelson to Kentucky to recruit and organize for the Union cause.

- July, 1861: William Nelson sends a request to the War Department for 300 carbines to used by the Mississippi Squadron, which was being formed by the Army.

- The Ordnance Department sends the order to Sharps.

- Sharps likely used the leftover receivers and stocks from the Mitchell contract rifles.

- The Sharps factory sent the carbines to the Army in New York where they were inspected.

- September, 1861: Army records show that 300 carbines were purchased for the Navy.

We can see that this is some solid new information about the origin of these guns. How far we’ve come since 1967 in our understanding of their nature! Let’s pause there and digest these ideas in Part 3.

Greetings,

Thanks for your research. I enjoyed reading your thoughts on the subject and am more convinced than ever that the unconverted carbines in this 300 carbine “Nelson” order were used.

You reference my comment posted on the Civil War Forum in regards to the USS Cairo and the incomplete listing of ordnance aboard. and I feel that might be more to the point than we realize but proof is can be an elusive rascal can it not?

My carbine is serial number 43223 and shows signs of service use. Bore is worn and it is evident it was used. Overall patina is even and it looks right.. From muzzle to butt plate it looks all the way like a gun that saw the elephant. If you ever want pics I can provide them. Best Regards Bill

Thanks Bill,

I really appreciate the kind words, and am grateful for that forum and all I can learn from you and others. Does your carbine have any cartouches on the stock? Or other markings at all?

Close inspection has brought up some authenticity issues.. There is not a cartouche on the stock. Stock has small block letters (2) that appear between sling swivel and trigger plate. I think an F and a J.. Other than that I find nothing, although area where cartouche would have been seems to be sanded and is smooth and slightly depressed.. I think cartouche got sanded off.

Of concern is that sling swivel is of the standard rifle pattern, Butt Stock appears way to new in matching the other patina of the carbine. Grain is still standing out and wear on metal is significant. Nipple appears new replacement and lock-late appears to be replacement based on corrosion comparison. Barrel band is pitted and does not match patina on barrel.

I suspect my sample is a composite gun made up to look like a Naval Contract arm. Disappointing but just calling it what it appears to be. Serial number is in the right area but This could have been a Mitchell Contract receiver, re barreled and restocked .. Barrel breech wear does not match the condition of the rear breech seal and plate either.